My Unconventional Life with

Autism

Good

evening. My name is James Williams.

The

title of my presentation is “My Unconventional Life with Autism.”

In

this presentation, I am going to tell you various stories. They will consist of

something that happened in my life or something I observed. Then I will tell

you what can be learned from each story.

I’d

also like to give the audience a warning. I’m going to use some terms and words

that might offend some of you. There is a portion of one story that some people

might find racist—this is because I am describing a story where racism was

perceived but was actually not a factor a all. I am also going to be making

jokes and criticizing teaching methods in school—a place where many of you

spend your days as a student or professional. I would like it if you took these

jokes humorously and not seriously, and these criticisms not as criticisms of

any individual teacher but of teaching methods in general.

I’m

going to start with something that I did when I was eight years old. My father

and I were taking a trip to Denver for the weekend. We went to O’Hare, and

boarded the plane. We were sitting in a three-seat row—a window, middle, and

aisle seat. I was promised the window seat so I could see outside.

My

father told me the number of our row, so I walked in front of him to get to our

seats. When I got to that row, a black man was sitting there.

I

waited until my father had gotten to our row of seats, and then he told to me

to get into my seat. I asked, “Do we have to sit next to that jerk?”

This

made my father furious. He made me apologize to the man. Then the man got up

from his seat and agreed to sit in the middle seat so that I could sit by the

window.

Why

did I call him a jerk?

The

black man tried to place the blame on my father, having assumed that I had made

a racist remark. My father was mortified, since he didn’t know the real reason,

and said that we lived in a very “non-diverse” neighborhood. The black man

believed I had called him a jerk because he was black.

There

actually was another reason, a reason that had nothing to do with race. While

it looked like I was being racist, I was actually trying to make sense of a

situation that did not make sense to me. You see, I had thought at the time that

when a specific group of people, or a single person, bought seats on an

airplane, they got the whole row to themselves. Since my father and I had

bought the tickets together, I thought that we had bought the right to that

row. I had traveled many times with my father, and we’d always ended up with a

row to ourselves. I had no idea people shared rows of seats together strangers.

Since

we had the right to this row, I thought, this man was a thief. And that made

him a jerk.

At

first, when I saw the man, I thought my dad might have made a mistake. Perhaps

he meant the row behind us, where no one was sitting. If that was the case,

then this man wasn’t a jerk. He was sitting in his seat, and I would not have

mentioned anything.

But

then my father asked me to sit in that row, and started packing our suitcases

in the overhead compartment. This was it for me. If this was indeed our row,

why was this man sitting in it? And why was my father not confronting him and

telling him to get out of our row? Why was my father letting him get away with

this?

So

I asked what was, to me, a logical question.

You

see what happened here? I thought something false based on what I knew, and

then I acted based on that false idea. It makes sense now that you know why I

did it. However, at the time, my statement simply seemed racist and downright

rude.

What

lessons can be learned from this event?

The

first lesson is that you cannot expect an autistic child to know anything, even

things that you think are obvious, unless he has conclusively shown to you that

he knows it. Because he’s autistic, he doesn’t necessarily know what you knew

at the same age. You might even find yourself in a situation where you can’t

even predict what he’s going to say or do. And you’ll be just as uncertain and

terrified that he’s going to embarrass you, as he is uncertain and terrified

that you are going to get him in trouble!

In

this case, my father not only expected me to know better than to call this man

a jerk, but it never even occurred to him that I might be thinking like this.

And the black man based his conclusion on what he knew—that it was racism.

Is

this mindblindness? Yes, but not intentionally. Thus, I’m not going to be too

hard on the black man or my father. When something doesn’t occur to you, it’s

not your fault you didn’t think it until someone mentions to you that you’re

wrong and you continue to think it.

When

you analyze it, parents, and people who know children expect a lot from them.

Parents assume their children will be rolling by six months, crawling by eight

months, walking by fifteen months, talking by two years, and ready to go to

school by age five. They do it without thinking, which is why it might seem

like such a shock to you when I point this out.

I

ask you, though—how many parents actually go up to their kids and ask them

whether or not they can actually do those things that they are expecting

them to do? Not many. And parents get away with it because somehow, if children

are not disabled or autistic, they are able to meet all of those expectations

given by them. And thus, the parent still thinks their expectations are

engraved in stone.

But

the autistic child doesn’t develop the same way. He doesn’t always talk at two.

I didn’t talk at two. The normal child reads at six. I read at three.

Differences in development work both ways—too slowly and too fast. But those

same expectations are imposed on the autistic child. And what happens to

parents when they see that their expectations are not being met? Often, they

get angry.

And

then the truth is revealed. These expectations only work with children who are

not autistic, or who are not mentally or physically handicapped, etc. That’s

because these expectations only came to be because of observations of normal

children, not disabled children. Thus, when you’re working with or parenting an

autistic child, you’re going to need to give some of your expectations up to

understand him or her better.

I’m

not saying that you should give up everything you expect from your child. But

if your child cannot meet your expectations then they’re not going to suddenly

learn out of the blue because you continue to expect them to know better. You

should still expect things from your child—but base your expectations on what

your child actually knows—not because he turned five three weeks ago. You

should also try to teach those skills to your child if he doesn’t know them.

But don’t expect him to pick them up on his own or just because you’re

expecting him to pick them up.

Scott

Bellini, a professional who works at the Indiana Resource Center for Autism,

once, during a presentation, asked an audience member to come up and say

something in Portuguese. The audience member could not. Bellini then offered

$50 if she came up and spoke Portuguese. The audience member still could not.

His point was that because she didn’t know Portuguese, there was no way in the

world he could get her to speak Portuguese to him—no matter how much money he

offered, or how much he expected her to know how to do it.

So

what’s the second lesson that can be learned?

Misbehavior

or acting spoiled doesn’t necessarily mean that you are spoiled. That’s

because it’s not your behavior that makes you who you are, it’s why you behave

that way. I called the black man a jerk because I thought he was a thief, and I

thought I was acting rationally.

If

you know you are behaving badly or inappropriately but do so anyway, you

may be spoiled. But if you think you’re behaving properly until your

parents, teachers, or strangers scream at you for being rude, selfish, and

inconsiderate, you might not be spoiled. You might just have autism or

Asperger’s syndrome. That happens all the time to people with autism.

I’m

now going to tell you about an earlier time in my life. It is not a specific

event but a yearlong experience—preschool. Preschool is not mandatory the way

regular school is, but many children are sent to it anyway.

I

was four years old when I first went to preschool. I don’t remember much about

what happened there. But here are my memories: when I went there on my first

day, I didn’t want to be there. When I got to class, I would walk in, attempt

to plunk myself down in a chair near one of the walls of the classroom, and just

sit there, all alone, by myself. Then lunchtime would be announced. I’d walk in

line with my class through a long hallway to a big room where we ate lunch.

I

would eat lunch with a small plastic fork, trying to ignore the other kids, and

then I would walk back to the classroom, and return to that chair. Finally it

would be time to go home, and I’d go back into that big hallway to find scores

of parents looking for their kids. I would walk around those scores of parents

until eventually I’d find my mother.

I

don’t remember learning anything, or doing much there, except that I wanted to

go home.

This

story is a confirmation of what I just talked about earlier—that to many

autistic people, like myself, their development doesn’t have much to do with their

chronological age.

To

be more specific, this story tells us that it’s not age that tells us whether

or not we’re ready to learn. Rather, certain “stages” of development need to be

passed before you can “learn” anything. Since most of these “stages” have been

passed by three, or four, or five, we assume that the child is ready when they

are three, or four, or five. But if you are four and have not gone through the

“two-year-old” stages, then you’re not going to be able to act like a

four-year-old.

I was

not ready to go to preschool even though I was four. In fact, it wasn’t until I

was seven that I even expressed an interest in doing preschool-related

material, when my sister started preschool.

As

of this writing (10/2005), I have another sister currently in preschool. I was

given permission to silently observe her for half a day. I got to see quite a

bit, and I’m going to comment on what I saw. This observation enabled me to

speculate as to why preschool is so difficult for kids with autism.

First,

to many autistic individuals, the sensory impacts of being in the classroom are

too much. The lights may be too bright. The constant noise of other kids is too

much for the child’s ears. So even before the teacher has done anything, the

child might be on overload, and this in itself is enough for a child to fall

apart. If the child cannot even stand the sound of the voice of the teacher or

the other children, he’s going to try to avoid them even if he doesn’t have

trouble with social skills.

At

the preschool I saw a constant war on isolation. No child was ever allowed to

be by him or herself for a significant period of time, that is, any more than

five minutes. If they were, the teacher would walk up to that child and start

interacting with them. Or another child would walk up to a child alone and try

to play with them. Or the teacher’s helpers would try to engage the solitary

child.

I

don’t know how many times this happened to me, but I can certainly tell you

that at this preschool, sitting down in one place by oneself was impossible

after five minutes. There would always be someone at each child, whether it was

a teacher or one of the assistants, trying to interact with these kids. An

autistic child would have wondered why such kids and the teacher were so

insensitive to his wish to be alone. “Why can’t you just leave me alone?” he

would be thinking, unaware that they are just trying to be friendly.

I

noticed one girl who spent ten minutes doing nothing but moving a wooden train

down a wooden track set. Why wasn’t anyone forcing her to be with someone else,

I thought? The answer was quite simple. Ten minutes later she went off to play

with someone. The teacher clearly knew this and didn’t get her in trouble. On

the other hand, she approached another child who didn’t know what to do and

started reading to her.

During

free time the teacher had a project where every child gave her a plastic tube,

which she connected to create a large plastic tube that she put around the

classroom. Then, she announced it was time for "clean up," and the

kids cleaned up. Then it was circle time, and after all the kids were seated in

a circle, the teacher called up individual kids for “show and tell.”

Interestingly, there were two boys who did not go to sit in the circle when

asked—they kept playing—until the teacher coaxed them to join the circle.

Such

things would infuriate an autistic person. Who are you to say I have to clean

up? Is that any of your business? Why are you forcing me to sit in this circle against

my will and watch other kids show things that I don’t care about? Why can’t you

just leave me alone? Why do you have to spend time-sharing something with me I

don’t want to see? Why do you care that I spend time with these kids?

All

of these questions might be circling through an autistic person. He has no idea

why he’s being forced to do those things by the “teacher.” To him, she is an

unpredictable stranger who might just yell at him at any moment, the way he

sees most people.

At

first glance, one could see that these are many questions that go through the

minds of neurotypical teenagers. That’s because the cause is actually similar.

The autistic person does not trust people, and believes he’s own his own, and

thus does not feel like he has to obey anybody. He feels as if he has the right

to make his own decisions, just like the teenager rebels against authority.

At

the same time, preschool is like an elevated two-story building that, instead

of lying on the ground, rests on constructed pillars that are on the ground.

The pillars consist of assumptions that, should they break, so would the

preschool.

The

first assumption is that it’s better to be with someone than be alone. That is

why everyone at that preschool was so relentless at getting the kids to

socialize, even the other kids. However, most autistic individuals like being

alone, so they see this negatively, just as you would be irritated by someone

who was always in your face every minute of the day.

The

second assumption is that the teacher is God, Der Fuhrer, Il Duce, Pharaoh, or

whatever you’d like to call her. Preschool is a constitutional monarchy. It’s

not an absolute monarchy because the teacher doesn’t have absolute power—her

powers are dictated by the rules of the school. She can’t abuse the children

but she reigns over the children. But it is a monarch’s dream, for the children

are absolutely loyal subjects. They think of her as the queen, and obey her

like the queen. Everything she told the kids to do, they did, and were even

happy to obey her. She was good, and she was wonderful. A despot’s paradise!

This

is connected to a third assumption, and that is, the assumption of universal

trust. Neurotypical children have a sense of basic trust. To them, everyone is

good and everyone is nice. That’s why they’re happy to obey. And that’s why

parents teach young children to “never talk to strangers.”

The

fourth assumption is that children are able to have empathy for other children.

During show and tell, when each individual child showed his or her toy to the

class, the class listened. The class was willing to be patient and not

interrupt the child who was showing the toy. And those children, in turn,

listened to the other children as they showed their toys. If a child did

interrupt, the teacher asked the child to be quiet.

There’s

also a fifth assumption here as well—that the child is able to learn the

preschool-level material. I wasn’t interested at four, but when I turned seven,

I suddenly was able.

At

the age of four, however, I was not ready for any of this. So, when these

assumptions were placed on me, I couldn’t meet them. My mother saw this and

decided to take me out of preschool.

In

my opinion, that is the best solution. If a child is suffering in school, you

should homeschool him if you can. However, I know that it is beyond many

parents to do homeschooling. So here’s what I’ll say about helping an autistic

child deal with preschool.

Hatred

is a very powerful emotion in autism. If they hate something, or hate someone,

then almost every attempt to get the autistic child to like it is going to make

them hate it even worse. On the other hand, if they like something, they’re

going to be willing to put up with certain things they don’t like if they like

it enough. This principle works for younger and older children—I disagree with

many policies at the daycare center I volunteered at but I put up with them

because I liked working at the daycare.

And

let us also heed the lesson of the Chinese finger trap. When the child doesn’t

want to interact, many experts say you should “step up” the behavior plans and

the discipline. In reality, this does nothing but motivate the autistic child

to “step up” their unwillingness to obey you. Like a Chinese finger trap, the

harder you push, the less likely your finger will get out of the trap.

Next,

the preschool teacher has to decide what her priorities are. What I think is

ironic is that it is claimed that “you go to school to learn,” yet there is

also a social side to school, and many parents get angry if they learn their

children aren’t making friends in school. Is it really essential to try to get

the child to make friends? Maybe it isn’t. Is it essential to try to get the

child to sit in circle time? Yes, it is. But just because he sits in circle

time doesn’t mean he’s going to listen to the child. However, you shouldn’t

force listening. In fact, you can’t force empathy on people. If they cannot

empathize, they will not empathize. The fact that you got him to cooperate

during circle time is good enough, so that everyone else doesn’t notice him.

The

preschool teacher also has to realize that if a child is not ready to learn the

educational material, he or she is not going to learn it. It took me until I was

seven in order for me to learn it. If a special curriculum suited for the needs

of the child can be made, then it should. A child like that should ideally be

in a special-ed preschool. If an autistic child is failing in a mainstream

classroom, despite the efforts of the teachers, then he needs to go to a

special-ed classroom, and if his parents cannot accept that, then that is not

the autistic person’s problem—that is the problem of the parents.

Similarly,

when you pursue friendships, do not try to pursue them in conventional settings

if they are not working in those settings. If preschool is not providing

friends for your child, don’t rely on preschool as a source of friendship. Try

to get him involved in safe settings where he can make friends and the kids are

not going to be meaning to him. Such examples are theraplay, or play therapy,

or integrated play groups.

But

history marches on, and after another failed attempt at preschool, and two

years of being homeschooled, I returned to school halfway through the 1995-96

school year, at the age of seven, as a kindergartner. And I loved kindergarten.

I didn’t hate a minute. And I remember why kindergarten worked.

What

made kindergarten work?

First,

the teacher was a nice, and understanding teacher. She did not say that I had

to spend time with the other children. In fact, I ignored the other children.

She let me work. I liked work. Work was something that I could do by myself,

and I didn’t have to worry about getting rejected by my work.

Second,

because I was much older than the other kindergartners, I was able to do much

of the work perfectly. Indeed, I kept asking the teacher for more work to do,

and she let me.

Third,

I was now interested in “kindergarten” stuff. With my sister in preschool, she

would come home and show her mother the projects she did. I wanted to do them

now. And preschool isn’t really that different from kindergarten. And that’s

why I was sent to kindergarten.

And

finally, there was no sense of being forced to do anything. Yes, I had to sit

in circle time. Yes, I had to leave when it was time to go. But I didn’t have

to do the thing I really hated doing—being with other kids, and the

kindergarten teacher also left me alone during free time.

After

kindergarten, I continued to periodically visit my former teacher in the fall,

and still do today.

So

what lessons can be learned from these positive memories?

First,

this is an example of what I said either—that whether or not an autistic child

feels forced to do something is very important. While this is not true in every

case, if an autistic person feels forced into something, and they don’t

understand it, they will often resist. I did not feel forced in kindergarten;

but I did in preschool. And even when I had to do something I didn’t want, I

would do it because I respected the teacher.

This

point is also part of a larger point—the need to understand, a need that, while

is greater in some people than others, appears among most people, neurotypical

or autistic.

It

is my observation that most people, no matter who they are, have a need to

understand what is going on around them. I also believe that this can be

demonstrated by science, religion, and ancient mythology. In my opinion, one of

the reasons why people have created religions is because it gave them knowledge

of how things work prior to having scientific explanations for them. Even to

this day people rely on religion to give them meaning in life.

Autistic

individual Temple Grandin, in her book “Thinking In Pictures,” has argued in

her book: “Since religion answers questions that science cannot explain, people

will always have a need for religion ever since they walk the Earth. Religion

survived when we learned the Earth was not at the center of the universe.”

On

a smaller scale, people have a need to understand why they are doing

everything, even neurotypical people. This might seem like a surprise but it’s

true. If a stranger walked up to you and said, “Give me your wallet, please,”

would you do it or resist him? You’d likely resist him. That is because you

don’t understand why you have to do that to please someone you don’t know.

But

wait a minute here. I’m sure many of you in your minds are objecting to

this. I don’t have a need to understand, you might be thinking. The

situation you just mentioned above might never happen to me, so why does it

count? If my friend wants me to do something, I go and do it. However, my child

with autism resists the fact that he has to come with me, and has a fit,

ruining it for me. Why is it that he resists but I’m willing to go?

In

reality, you both have a need to understand. In this case, it’s because you

understand why you have to go—because your friend wants you to and you like

your friend. In that other situation, whether or not you’ve been in it, you

would not understand.

But

your child likely hates your friend, and doesn’t understand why he has to go

there. He does not have that sense of basic trust toward you, and for that

reason he’s not going to do something just because you want him to do it. He

has to have a reason that benefits him. This is not selfishness; this is a

logical response of those who do not trust anyone else. It only appears to be

selfishness because most kids pass this phase by the time they’re five, and are

trusting everyone. But the autistic person does not.

Or

he’s gone to the other extreme—trusting everyone too well, and getting taken

advantage of by his attempts to obey people. Some autistic people will be so

obedient that they’ll hit a teacher if a child asks them to—and get in trouble

with the school, or even get thrown in jail.

So,

how is the need to understand usually met?

The

need to understand can be met by motivation. Should the stranger go further and

offer you $1000 for your wallet, you might accept because you want the money.

Or you might still say no, because you still don’t understand why this person

is being so persistent. Should you accept, you understand why you’re doing

it—to get the $1000. You have an incentive to strip because of the money.

Should you not accept, you don’t understand why he’s offering you the money,

and that’s not a reason to embarrass yourself.

The

need to understand can also be met by trust. This is especially true for

younger kids who will do whatever you tell them to because you’re their mother,

or their teacher. This trust also occurs between me and kids at the daycare as

well.

Finally,

the need to understand can also be met by force. A child who is misbehaving

does not understand why the adult is enforcing a rule, and does not follow it.

Then the adult threatens a punishment and the child obeys. If the punishment is

undesirable, or causes suffering, then the child will obey. But if the

punishment is not a deterrent, then the threat of punishment will be futile.

But even if the adult gets the child to obey, that doesn’t necessarily mean the

child respects the adult any more.

This

is also important because if there is no understanding, then in some autistic

kids, there will be fear and resistance. Because autistic kids do not

understand why they have to do things that their fellow neurotypical peers

understand quite well, they often resist, and this in itself is enough to cause

a child to resist something and have a fit, even if the event is not causing

them any pain due to sensory issues. I

have resisted many things not because I couldn’t stand the smell or the noise,

but because I didn’t understand why I had to be there. This was the case when I

was forced to attend my cousin’s wedding at the age of seven.

So

how do we try to resolve this problem? Create understanding, at the level the

child is able to understand—no more, no less, if you know what that level is.

One of the ways this has been illustrated is with Social Stories, a method

popularized by Carol Gray. Social stories are a good way of explaining why

something has to happen, and if successful, you can give an autistic child the

understanding that they need in order to behave properly and not resist.

This

is not to say that all meltdowns and resistance are due to a lack of

understanding. Sensory issues and an understanding that is wrong

(misunderstanding) can also be the cause. But they are sometimes the same

issue. An autistic person may not understand why they have to do something

because it hurts their ears or lights, which makes them resist. In these

situations, however, just because they understand doesn’t mean they won’t

resist. If something causes them pain, they’ll try to get out of it because of

the pain, just as anyone without autism will try to resist someone who is

beating them up even if they might understand why that person needs to beat

them up.

For

this reason, if an autistic child is resisting due to pain caused by sensory

issues, or due to fear, a social story is not going to change that. You are not

going to get a child to stop being terrified of fire drills no matter how many

times he learns why they have to take place if he feels pain when they suddenly

occur. When I was terrified of the fire drill in school, I learned as much information

as I could as to why our school had them, but that didn’t stop me from feeling

hurt whenever I heard the noise.

But

history marches on, and after kindergarten, I went to second grade. That was

hell, and so my mother pulled me out halfway through the year. I didn’t return

to school until I got to fourth grade. And fourth grade was a successful year.

The kids were not all nice to me, and once again, I made no friends there, but

I had a nice teacher, which made the year successful.

What made her year so successful as well? That was because of mutual

compromise. She agreed to honor me and respect me as a person, and overlook the

minor mistakes I would make. She even started the first day of school by

stating that she was ten times as forgetful as we were. When I heard that

statement, I knew that year would succeed.

Probably

one of the best things she did for me was her policy of applying logic to each

situation. She would never just enforce a rule or deny someone something

without giving a logical reason for it, and seemed to have indefinite wisdom

and logic. She also acknowledged that something that was bad in one situation

might not be bad in another situation. For example, when she gave us an

assignment to write an autobiography, I asked if I had permission to write

portions of it at home. This was so I could type it, because handwriting was

difficult for me at that time. She said yes. Then she told the class a story of

a student who had also tried to gain that permission, only to later learn the

student had actually tried to not do the assignment at all. This shows wisdom

on her part; the fact that a student in the past tried to get out of the

assignment doesn’t mean I would, nor would she have to make it a rule that no

student could do the assignment at home. And I didn’t betray her trust. Rather,

I made sure she knew by showing proof to her that I was doing the assignment

daily until she no longer needed proof.

Every

night, I was required to read for a half-hour, and then write a summary on what

I had written. Because handwriting was difficult for me, she let me type my

daily summaries of the book, and I could give them to her typed.

Because

of her methods, some kids tried to trick her into getting out of assignments.

But she always caught them, and retained her wisdom at the same time. For

example, she always let me leave the room without telling her when I had to go

to various special meetings I had, such as a visit to the speech therapist or

the social worker. On the other hand, two other children who asked to go to the

library to do research only to just twiddle their thumbs on a chair for 90

minutes were not allowed to leave the room again without permission.

These

examples illustrate that it’s your motive behind your behavior, not your

behavior that determines your personality.

My fourth-grade

teacher was also enlightened about certain issues children might have, even if

they weren’t autistic. For example, she took it for granted that some children

might have trouble taking notes—so whenever it came time to do note-taking, she

wrote what she was saying on an overhead projector as well as saying it, to

make it easier for us. She also constantly reminded us that if we needed more

time, all we had to do was raise our hand and she’d give it to us. With these

easy accommodations, she mitigated what could have been a very stressful

situation for me.

She

also acknowledged my right to be alone. In our classroom, we had neighbors we

sat next do. A person’s desk would be next to someone else’s desk. On the other

hand, I was given the right to sit alone with my desk without any neighbors,

and I admired her for that. She would always keep me in the same place even

while she moved her neighbors.

I’m

not saying she was perfect. She didn’t do as much as she could have to stop

kids from teasing me, after all. But she did something else—she would often let

me be alone to protect me from teasing.

What

can we learn here? Basically, that in some cases, the solutions to solve

problems with autistic children really aren’t that difficult. I had a great

year with her, apart from the teasing.

I’m

now going to talk about another observation. In this case, I’m going to discuss

an issue that takes place in school. While is an important issue for some, is

not one of the issues usually discussed with autism and school, and not

initially thought of when we think about the problems autistic kids face in

school. It is, however, an issue that still affects autistic individuals.

First,

I need to warn you that this observation is not autism-friendly. If you’ve got

autism, or any autistic spectrum disorder, I would advise you to leave the

room.

[Wait

until everyone has left.]

I’d

like to introduce this by giving you a background about some research I’ve done

this year that is very useful for those who want to understand A.I.T.

All

sounds, speech, music—that is, what we hear, is heard by our ears on different

frequencies—

[NOTE:

The following is a link to a recording of a real fire alarm, so be careful

before you sound it if you are on a public computer or in a building with a

fire alarm system—people might think the fire alarm is really going off if they

hear it.]

--that

are measured in Hz. Some sounds are on low frequencies, and some are on high

frequencies. For tones, the pitch of the tone determines the frequencies it is

going to be on.

[The

fire alarm is silenced.]

All

right, I’m going to stop now for an obvious reason. You have all been treated

to a sound that terrifies the souls of many autistic individuals daily. You

have just heard the sound of a fire alarm, one of many fire alarm sounds that

are heard in schools all over the world when there is a fire drill. Compulsory

suffering for an autistic person.

This

was the sound of the alarm at the school I went to. The day I learned I was

sensitive to sound again was the day we had a fire drill, and suddenly the

sound I heard was not just an alarm but also a shock. I felt like I had been

jolted by electricity. I will remember that feeling for the rest of my life.

Fortunately,

I now am in an environment where I am not subject to such loud, sudden sounds,

so my sound sensitivities do not affect me as much.

This

year, however, I decided to go on a quest to try to see why the sound of the

fire alarm is so terrifying. What I have found out might interest you.

When

we hear things, our ears process them on different frequencies. These

frequencies are measured in Hz, and whether or not the sound is on a high or

low frequency depends on the tone or pitch of the sound. People who have

sensitive hearing typically are not sensitive to all sounds equally—rather,

they are more sensitive to some frequencies than others. Thus, the concept of

the treatment known as Auditory Integration Training is to retrain the hearing

to not hear those frequencies as well so that the person is less sensitive to

them.

Sharon

Hurst, an A.I.T. practitioner, has told me that one common feature of people

with sensitive hearing is that they can hear between the 1-8 KHz range very

well, and thus are sensitive to that range. She also has told me that most

people who listen to hard rock music or play loud instruments have gone deaf at

around 4Khz.

I’ve

also discovered that, by using Windows Media Player 9 (music-playing software

that runs on Windows 98 or higher) it’s possible to chart how high or low a

song or a sound is on certain frequencies. Windows Media Player 9 has certain

visualizations that you can turn on that are generated when a sound file is

playing. One of those visualizations is called “Fire Storm” in the “Bars and

Waves” section. This visualization allows the viewer to see these frequencies

in the form of sound waves, which have the similar shape of an audiogram. I

played the sound of the fire alarm on an MP3 format in Windows Media Player,

and it showed me where that sound lies on frequencies between 31Hz and 16Khz.

So now I’m

going to show you what Windows Media Player revealed about the sound of the

fire alarm.

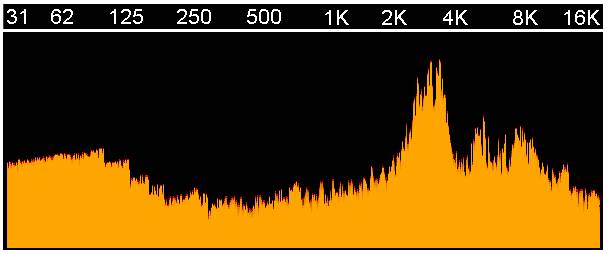

Frequencies (Measured in Hz)

Fire Alarm Frequency Chart

The

numbers on top represent numbers of frequencies measured in Hz, with the higher

numbers representing higher frequencies and the lower numbers representing

lower frequencies. And the loudness of the sound is represented by how high or

low the wave is.

Now let’s take a look at this

diagram and see what it shows. You see anything interesting? It starts here,

goes down a little bit, and then there’s a peak between 2-4Khz. What this tells

us is that this fire alarm sounds a lot higher at 2-4Khz then another

frequencies. Now let’s remember what Sharon said about most kids having

sensitive hearing between the 1-8 Khz range. And I’ll also add the fact that

Sharon also has said that 4Khz is the frequency damaged the most in ears of those

who listen to loud hard rock music or are exposed to loud noises frequently.

When all of this information is stated together, isn’t it any wonder this

sound, and sounds like this in other fire alarms, terrify an autistic child?

Now

I’m going to tell you the final story of my presentation.

Since

the winter of 2005 I have been volunteering at a daycare center in my hometown.

In the summer I witnessed a neurotypical six-year-old girl revert to behaviors

associated with autism.

The

problem was not just the fault of the daughter. The mother was equally

responsible. But of course, only the daughter was punished.

So

one day at the daycare center, in walk three children—two girls and a boy. The

six-year-old girl sits down in a rocking chair.

I

am busy playing with another child, so I continue my game and ignore them. Then

I hear a loud screaming sound in the distance. I look over. It’s her.

She

screams, “I want my mommy! I want my mommy!” One of the staff members says she

will get her mommy. “I want her now!” It’s a bluff because I know it is

extremely unlikely her mother is going to come back. No parent ever has before.

I don’t look to see if the staff member left the room to ask, but her mother

doesn’t come back anyway. I look back at the kid I’m playing with and we

continue our game. While we keep playing, I try to tune out the screaming in

the distance. When the screaming stops, I look at the girl. She is now silent

and frozen, still sitting in the chair. Her face is filled with tears.

The

game I’m playing ends. With the girl calmed, I approach her. We start playing.

And she has a good time. She lightens up. And then, the mother walks in. I tell

the girl her mother has returned, and she runs to her mother.

Her

mother says to her, “You misbehaved. You did a bad thing and you need to

apologize. Say you’re sorry.”

The

girl looks at her mom and says, “No.”

“Say

you’re sorry.”

“No.”

“Say

you’re sorry.”

“No.”

The

girl tries to get away from her mother, but her mother grabs her hand to stop

her from escaping.

“We’re

not leaving until you say you’re sorry.”

“No.”

“Say

you’re sorry.”

“No.”

“We’ll

stay here until it closes if you don’t say you’re sorry.”

“No.”

“You

know, everyone is hungry for lunch. Your sister wants to go home. So just say

you’re sorry.”

“No.”

I

sit down in a comfortable chair and witness this, eyeing the clock. This goes

on for another ten minutes. I am silent. Obviously I didn’t go off and lecture

this parent, nor did I tell her I was going to castigate her in a speech.

“Say

you’re sorry.”

“I’m

sorry,” the girl says very softly.

“Say

it nicely. Say it.”

While

this is going on, her younger sister, a four-year-old, says to her mother, “I’m

sorry, Mom. I’m sorry” constantly.

“You

didn’t misbehave. Your sister did. She has to say she’s sorry. Now, do you want

to go home?”

“Yes,”

the younger sister said.

“Then

tell your sister to say she’s sorry so we can go home.”

“I want

to go home,” the younger sister said.

“You

see? You’re hurting your younger sister. Say you’re sorry.”

“No.”

“I

can’t take this anymore. Say you’re sorry.”

“No.”

“All

right. We’re staying here until you say sorry. We won’t even go on the trip

we’re taking this weekend. Say you’re sorry.”

“No.”

So

another ten minutes pass with the girl refusing to say sorry. By now she’s

trying to get away from her mother and resorting to scratching her mother’s arm

to get away.

“Say

you’re sorry.”

“No.”

Finally

the girl, defeated, goes up to the staff member and says, “I’m sorry.”

Then

they leave. On the way out, her mother looks at me and says, “Thank you for

being with her.”

So

what’s the lesson that can be learned? First, this demonstrates just how

out-of-hand a situation like this can get. The mother and the staff members

blamed it all on the six-year-old—when in fact the mother was just as much at

fault as her daughter. Her daughter was wrong to talk back to her mother. Her

daughter was wrong to scratch her mother. But her mother was equally

responsible. In fact, you could say that the mother did it to herself. She

didn’t come for her daughter, and then had to nerve to ask for an apology and

to call it misbehaving. But all her daughter was doing was showing some emotion

towards her mother, and she got punished. What is she teaching her child? Not

only that her feelings do not matter, but showing love toward your own mother

is misbehaving.

I’m

not faulting the mother for not coming back to her daughter when her daughter

had a meltdown. I am faulting the mother for making a big deal out of that

meltdown instead of comforting her daughter and reassuring her that it was

okay. I am also faulting her for asking her to apologize and then escalating it

for twenty more minutes. Then she put her daughter on the spot by somehow

making it HER fault that her younger sister was going hungry and that she

didn’t go home. It’s the mother’s fault, not the younger sister’s!

As this

shows, meltdowns are not uniquely autistic. This girl had no autism in her—yet

she still melted down. But the process is still the same. The child is put in a

situation they cannot cope. They are unable to escape, so they fall apart. Since

autistic people are put in more situations they cannot cope with, they fall

apart many more times.

You are going to have to listen to an autistic

child if you want to prevent a meltdown. This might seem unthinkable, but is it

really? Is it really worth fighting a child who is suffering if you could just

compromise and accommodate the child? No.

To conclude, I can simply say the following. In

my short life, which is still unfolding, and in some ways is just beginning,

I’ve seen quite a bit. I’ve been through a lot. I’ve witnessed a lot of stuff.

I’ve done a lot of thinking, made a lot of mistakes, made a lot of messes, but

got through them. In some ways, I’ve done more things than other kids my age.

In other ways, I’ve done very little. My life is not conventional. But it is

still a life I enjoy, and a life that accommodates my autism.

Well, I’m going to stop here and answer any

questions you might have.

[Postscript, written on June 6, 2006]: While I

have just told a story in which I have portrayed a parent negatively, and do

believe that how the parent handled this situation was wrong, this does not

necessarily mean that this person is a bad parent. Parents, like all people,

have good days and bad days, and often will get angry at their children. People

who are angry get irrational--there is nothing wrong with this. Everyone has a

right to let their anger out. For this reason, we should not entirely judge a

person when they are angry, nor should we argue that if a person says something

negative when they are angry, they truly believe it once their anger ceases.

But it also means that after a person is done getting out their anger, they

should try to understand what got them angry and to think about what can be

done to prevent that anger from coming again, or to find another way of solving

a similar problem in the future. For this reason, the intention of telling a

story like this is not to insult this parent or parents in general, but rather

to see how a problematic situation formed in the past so we can learn from it

to help us in the future.

[Author’s note: Portions of this speech can also

be found in the speech “Auditory

Training: My Personal Experience and Thoughts,” “Understanding: The Free Therapy,”

“The Role of Context in Defining

Autism,” the speech “What to

Do During an Autism Cataclysm.”]