Researching Issues of Autism and

Characters with Autistic Tendencies in Children’s Literature at the Center for

Children’s Books (2015)

James Williams

The following is a combination of two linked papers

written for the graduate assistants and librarians of the Center for Children’s

Books at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, after conducting

research at the library during the 2014-15 school year.

Introduction

I am an adult with autism that has worked in the field of autism awareness for the past 16 years. Since I have autism, I am commonly referred to by my colleagues as a “self-advocate” in the field. I am also the author of three children’s books about autism—the novels Out To Get Jack and The H.A.L. Experiment, and the picture book When Gary Comes to Play.

As a self-advocate, one of my interests has been analyzing issues of autism, as well as characters with autistic tendencies, in children’s literature. This interest originates from my experiences as a young child growing up with autism. As a child, I routinely struggled to relate to other children. However, I enjoyed to read, and discovered, as I grew older, that I could relate well to many characters in children’s books. I often felt that many characters had tendencies of autism, or were in social situations that I often struggled with.

My favorite books were books from the Ramona series and The American Girls Collection historical figures series, since I felt like I could relate well to the characters in these books. Ramona Quimby, the main character of the Ramona series, acted in ways very similar to a child with autism. And although the historical figures did not have autism (the term didn’t exist back in their historical eras), the girls often expressed frustration with the social expectations of their era (especially Felicity and Samantha in their book series), and I related to that since I often felt frustrated with social norms of the present day.

When my lecturing and writing career began, one of the subjects I wrote about was how experiences of autism appeared in literature and films. However, I took the approach differently than other conventional approaches. Rather than discuss literature and films about people who were openly diagnosed, such as the book The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night Time and the film Rain Man (a film that was, especially in the United States, the general public’s first exposure to autism), I decided to look at literature that indirectly referenced autism.

My research led me to write several presentations on this subject, primarily “Check It Out! A 3rd Grade Autism Reading List,” and “Autism’s Appearance in Books and Film,” both written in 2006, which have sections that overlap. Another presentation I wrote is “Harry Potter and the Chamber of Autism,” a presentation written for an upper elementary school audience that teaches autism awareness via references to Harry Potter books.

In addition, I have also met and worked with Lynn Stansberry-Brusnahan, a professor at the University of St. Thomas, in Minnesota. Stansberry-Brusnahan has written about how children’s literature can be used to teach social skills and autism awareness, and her work has inspired and shaped my work as well. And many of the same American Girl books that I enjoyed as a child are now recommended by Dr. Brenda Smith-Myles and other professionals in the autism field as good books for children with autism to read for social skill development.

The research for this paper was conducted at The Center for Children’s Books (CCB). The CCB refers to one of the libraries of the Graduate School for Library and Information Science (GSLIS), at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, in Champaign, Illinois. Located on the lower level of the University’s Graduate School for Library and Information Science (GSLIS) building, the CCB is a reference library that consists of a large collection of children’s books. The library is open to the public, and publishes the Bulletin of the Center for Children’s Books.

During the spring and fall semesters of 2014, and the spring semester of 2015, I paid multiple visits to the CCB to conduct research for this paper. I read countless children’s books to look for books that, to me, had the most relevance to the autism community, and featured characters with autistic tendencies.

The librarians were supportive of my research and I thank them for their input and advice during my project, especially graduate assistant Alice Mitchell.

This paper is divided into two parts that originally were presented separately when first written, but have been combined for the purposes of simplicity. Part 1 consists of a list I comprised from my research of autism-relevant children’s literature. This list describes 7 individual books, from the dozens of books that I read during my visits to the CCB, that I felt had the most relevant parallels to issues in the autism community, and 3 popular book series that I enjoyed as a child and partially reviewed at the CCB. Part 2 consists of a more detailed analysis of 3 of the 7 books I read and reviewed, in the form of 3 case studies.

Part 1: A

Reading List of Individual Books + Book Series with Issues of Autism and

Characters with Autistic Tendencies

The opinions shown for each individual book are my observations and most definitely do not reflect the opinions of the authors of this book. Indeed, the purpose of this list is to show how authors can inadvertently incorporate issues of autism into their books without necessarily realizing it.

The book series in this list refer of series of books that, when I read them during my childhood, I felt I could relate to because of experiences with my autism I felt that I shared with characters inside the book series.

I shall summarize each book, and then write a paragraph in italic regarding how, in my opinion, the book relates to an issue that people with autism face, and/or how the book features characters that have tendencies of autism.

Individual Books

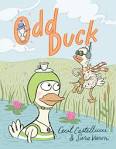

1. Odd Duck by Cecil Castellana and Sara

Varon

Theodora, a duck accustomed to a specific daily routine in life, meets Chad—a duck who behaves very differently than her and sometimes behaves downright offensively. However, as Theodora gets to learn more about Chad, she slowly realizes that Chad and her have a lot in common, and a friendship between them emerges slowly but surely--despite judgments that other ducks have about them and their friendship.

This book parallels

some of the struggles individuals with autism have in making friends, as well

as the different ways that people with and without autism perceive one another.

2. 6th

Grade Can Really Kill You by Barthe deClements

Helen Nichols struggles with reading, is learning disabled, and often misbehaves in school. Her parents are initially hesitant to agree for her school to give her special education services she needs, until they realize that may be Helen’s only hope. Finally, an enlightened teacher, Mr. Marshall, is able to get through to Helen and help her take the first step in improving her behavior and her performance in school.

This book parallels

many of the struggles individuals with autism have in a school setting and the

struggles many parents face when coming to terms with their child’s need for

services. It also serves as a nice way of comparing and contrasting the issues

that people with disabilities related to autism have versus individuals with

autism.

3. Breathless by Jessica Warman

Katie Kitrell loves to swim. She enjoys being on the swim team at Woosdale Academy, the boarding school she attends. She has an older brother named Will, who is very disabled and has violent tendencies related to his disability, which embarrasses and frustrates Kate. At Woodsdale, Kate hopes to escape the struggles she has with her sibling and hopes that they do not affect her socially, and puts her energy into her academics and the swim team. She also starts dating a student named Drew. But Will takes a turn for the worse—and eventually Kate’s ability to keep her secret about her family at Woodsdale is compromised.

This book shows

awareness about the struggles that many families face who have children with

autism that have violent tendencies, especially siblings. It also describes

much about swim team culture and the culture of swimming. Interestingly,

although Katie is not disabled, her passion and chosen sport—swimming—is very

popular among many people with disabilities and very calming to them. But what

I like most about this book also describes many of the issues and struggles

that violent kids like Will face as well, and shows that, they are struggling

just as much as their families. The issues of violence are not as one-sided as

many people might think.

4. Hug Machine by Scott Campbell

A little boy who hugs people calls himself the Hug Machine—and he hugs almost everything in sight. His hugging is powered by energy he gets from pizza. But what happens when he runs out of energy?

Like the boy who

identifies himself as the “Hug Machine,” this book is very allegorical to the

“squeeze machine” that is sometimes used in the autism world to give hugs to people

with autism who often rely on being hugged and “squeezed” to calm themselves

down from a sensory overload. This machine was invented by individual with

autism Temple Grandin who had a need to be “squeezed”

but wasn’t always able to hug people when she needed a hug. Not all individuals

with autism need hugs (some are actually tactile sensitive), but those who do

sometimes find themselves in this situation.

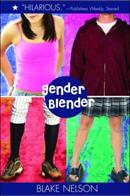

5. Gender

Blender by Blake Nelson

Emma and Tom used to be friends, but are no longer friends in middle school. Tensions emerge when they are both assigned to work together on a report on gender differences. What makes things worse is that after an unusual accident on a trampoline, Emma and Tom’s minds switch into each other’s bodies—and now, they have to learn how to live as a person of the opposite gender, and work together to cope with the awkwardness that each gender brings. The switch is discovered to be tied to Tom’s Native American arrowhead, which turns out to have been cursed. Can Emma and Tom reconcile, and do whatever it takes to switch back?

I enjoy this book because this book teaches

awareness of the impacts of gender expectations on middle school children. Many

of these gender expectations are similar to the gender expectations that children

with autism struggle with, while they are often embraced by their same-gender

peers. In addition, I admire this book because it is open about many of the

awkward issues that boys and girls endure equally through Emma and Tom’s

experiences, and it shows how boys are just as much a victim of stereotyping as

girls are. Perhaps, as the book suggests, many of the “bad, annoying” behaviors

that boys exhibit are the product of this stereotyping, similar to how we

associate many negative pressures exerted on girls from this stereotyping.

- The Goats by Brock Cole

Two children—Laura and Howie—are stripped naked and abandoned in a prank at summer camp. After coping with the initial awkwardness of the ordeal, they decide to run away from camp together. Surviving on their own until they can get picked up by Laura’s parents, since Howie’s parents are unable to reach them, they become close friends, and learn a lot about themselves in the process.

This book teaches

awareness of many common themes not just among kids with autism, but other

disabilities. Laura, in fact, identifies herself as having a social disability.

Laura and Howie start out as victims of bullying that

are commonplace among kids with autism (who are often sadly selected more often

for pranks), and Laura’s social disability results in her having social issues

that children with autism commonly face. Portrayals of Laura and Howie’s friendship show awareness of the close cross-gender

friendships common among children with social disabilities. I also admire this

book because it also brings up the subject of menstruation and how it applies

to Laura’s disability through dialogues between Laura and her mother—today,

much research has shown that many girls with disabilities have major struggles

coping with menstruation, and that some girls with disabilities have to cope

with the symptoms of their disability magnifying on or before their menstrual

cycle.

7.

Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle by Betty

McDonald (1947)

Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle is an expert in

her community on raising children. Parents come to her whenever they feel

frustrated over their children’s “bad” behaviors. They sometimes consider their

children to be “bad” children. Through several stories of many unconventional

cures towards “bad” behavior, Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle

shows the parents, and their children, how to change their behaviors for the

better, and that their children may not be so “bad” after all.

Since this book was

written in the late 1940’s, when attitudes toward parenting and disability were

quite different, this book reveals how many “problem” behaviors, many of which

are commonplace among children with autism, were perceived at the time as being

behaviors of “bad” children. Many of the behaviors, however, that the children

in each “story” display (that Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle is

asked to give cures to,) we know today can be attributed to autism and other

disabilities as well, and that not all children who exhibit those behaviors are

“bad” children. Although Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle does not

consider the idea that the children she is curing may be disabled, she does

share the same message that is known today in the disability community—that the

children she is “curing” may not be “bad” after all—they may be just disabled

or misunderstood.

Popular Book Series

8. The Ramona Quimby Book Series, by Beverly Cleary

This book series by Beverly Cleary chronicles the adventures of Ramona Quimby, from age 4 to age 10, a girl growing up in Portland, Oregon. Throughout the series, Ramona often struggles with understanding adults and others around her, and behaves in ways that confuse many people. By the end, she retains her imagination but is more able to understand the differences of others around her. However, as one of the books describes, “anyone who knows Ramona knows that she is never a pest on purpose.”

The Ramona Quimby book series portrays the development, from early

child to school-aged childhood, of a young girl whose behaviors and tendencies

mirror and parallel common behaviors and tendencies seen among children with

autism. In addition, like many children with autism, Ramona tends to upset

other people, even though the book reveals that Ramona never tries to be a

“pest on purpose.” Growing up with autism, I felt like I could relate to Ramona

because of those very behaviors and tendencies that I myself often engaged in

as a child.

This book can also be

used to teach awareness of the “gender gap” in diagnosing autism—research

initially conducted by psychologist Dr. Tony Atwood, and furthered by

self-advocate Dena Gassner, has shown that due to

cultural and diagnostic biases, girls with autism are less likely to be

diagnosed with autism than their male counterparts, even when they exhibit the

same symptoms. Ramona’s displays of autism despite the lack of consideration by

anyone regarding the possibility of a disability is still seen today among

girls with autism, who often grow up feeling

frustrated not knowing the true cause of their differences.

9. The Harry Potter

Book Series, by J.K. Rowling

J.K. Rowling’s well-known Harry Potter series chronicles the life of Harry Potter, the orphaned son of two powerful wizards as he negotiates his education at the Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry, and trains to defeat his lifelong enemy and nemesis—Lord Voldemort, an evil wizard that Harry has been destined to defeat through several magical prophecies.

The popular and

best-selling Harry Potter series does not always parallel issues of autism, but

several scenes and characters in the book series do. Luna Lovegood,

a Hogwarts student introduced in the 5th book of the series, is

sometimes considered to be on the autism spectrum by Harry Potter fans. Other

scenes that parallel situations related to autism are as follows—the social

anxiety that Harry Potter experiences in the 4th book when trying to

find a partner for the Yule Ball which is similar to the social anxiety that

kids with autism experience, and the reaction to the cry of the seedling

Mandrakes that can leave a Wizard unconscious in the 2nd Harry

Potter book parallel different, but similar negative reactions that children

with autism that have sensitive hearing experience when they hear loud noises.

10. The Twilight Saga, by Stephanie Meyer

Stephanie Myers’ well-known Twilight Saga tells the story of Bella Swan, a teenager, who moves to Forks, a small town in the state of Washington. There, she meets vampire Edward Cullen and werewolf Jacob Black, and falls in love with vampire Edward Cullen. Conflicts emerge, however, between Edward and Bella due to their differences as a human and a vampire. Edward breaks off the relationship, fearing for Bella’s safety, and Bella falls in love with werewolf Jacob. Eventually, a romantic triangle emerges between Bella, Edward, and Jacob, and a series of outside events requires Bella to choose between Edward or Jacob.

Parallels of autism

can be found mostly in the first two books—Twilight and New Moon. In Twilight,

Edward shares to Bella that he cares about other humans and that he tries to be

a good individual, but as a vampire, the world often sees him only as a killer,

because he is a vampire. Likewise, many individuals with autism often are

viewed negatively by society, even when they are honorable, moral individuals.

People with autism often are stereotyped negatively, and sometimes, people with

autism are mistaken as criminals and bad people by others who do not understand

them. Another parallel occurs when Bella visits Edward’s family for the first

time. Bella is unsure on what the social expectations are when visiting a

family of vampires, and whether or not she will be

socially accepted by them. This parallels the common social struggle that

individuals with autism have understanding unwritten rules in many social

settings.

Finally, in the 2nd

book, New Moon, the strong depression that Bella experiences when Edward breaks

off their relationship and feels rejected by him parallels the strong issues

that many people with autism who desire friendship and social interaction feel

when they experience rejection from other people. And many of those individuals

experience such rejection frequently due to their social deficits. In addition,

just as Bella feels unsure as to why Edward rejected her, many people with

autism, due to those same deficits, often find that they are unable to truly

understand why they have been rejected, and that others have not given them an

adequate explanation as to why they were rejected. And sadly, this often makes

them unable to learn from the rejection or move on from it, even when many

years have passed since the rejection occurred.

Case Study #1: Odd Duck, by Cecil Castellucci

and Sara Varon

(First Second Books,

2013)

Odd Duck was the first book I read for the research project. It was recommended to me by graduate assistant Alice Mitchell. In Odd Duck, I saw a children’s book that, through the plotline of two anthropomorphic ducks, tells a story of two ducks that parallels many social interactions, social struggles, and cultural issues that individuals with autism face.

Odd Duck is a picture children’s book that tells the story of the interactions between two anthropomorphic ducks (who act like adult humans, and who live in human-like structures) who initially struggle to understand one another, but eventually become good friends. Through the adventures of the two ducks, the author teaches a social lesson about acceptance and understanding of differences, and the idea that two different individuals can still be good friends. Like most allegories, telling the story in such a context—in this case, amongst two ducks--makes the message more understandable, as well as more acceptable, to its intended audience. Should the story have been between two human children, regardless of age, it may not have been as well received to its intended audience.

The story begins with the introduction of the female duck Theodora. It describes her daily routine and describes her as preferring to live alone. Things change, however, when a new duck, named Chad, moves into the house next door to her house. This scares Theodora, as it threatens the solitary existence she has grown accustomed to. Making things worse, Chad behaves in ways that are strange to Theodora. As the seasons change, Theodora attempts to continue her routine and her daily life alongside Chad. However, many of Chad’s behaviors annoy Theodora. She hopes that he will fly south with the other ducks for the winter (even though she chooses not to), but he does not either. During the winter, Theodora and Chad become friends. Their friendship is challenged in the spring when other ducks judge Chad, which causes them to have an argument about who is the “odd duck” in the relationship that almost ends their friendship. They decide, in the end, that they are both a little odd, but they can still be friends, and that’s okay.

Many references and connections to autism appear in this book. The story parallels a common narrative that often occurs within a friendship between a non-autistic (neurotypical) person and a person with autism starts, and the happy ending of the story reflects the common things that occur should such a friendship be successful in the real world. Although different in the specifics, this narrative occurs among such friendships at different ages and stages of life.

To describe this comparison in greater detail, I shall demonstrate how key parts of the story parallel the social issues mentioned above. For the following narrative, I have written the comparison to social issues among individuals with autism in italic.

First,

Theodora’s behaviors and routine are described. Likewise, people with autism are often people of routine.

Second, she meets Chad and is annoyed by what she believes are odd behaviors. Likewise, when a person with and without autism meet, the non-autistic person is annoyed by the person with autism. In addition, many of Chad’s specific behaviors are quite common among people with autism, such as “talking a mile a minute” (if the person with autism is verbal), are common among people with autism.

Third,

Theodora tries to ignore Chad despite Chad’s attempts to be friendly towards

her, implying he is unaware of how he annoyed her. Likewise, many people with autism are not always aware of how their

behaviors annoy others around them.

Fourth,

Theodora realizes Chad is not as annoying as she thought and they become

friends. Likewise, many people without

autism often find that people with autism are smart and make good friends after

looking beyond the annoying behaviors.

Fifth,

Chad is judged by other ducks when Theodora takes him into town, but Theodora

is accepting of Chad’s idiosyncratic behaviors. Likewise, many people without autism experience this as well—their

friends with autism are often judged by their friends and people in their

community when they go out in public.

Sixth,

although Theodora feels sorry for Chad being judged, Chad reveals that he feels

sorry for Theodora, leading to an argument that almost costs them their

friendship. In this argument, both Theodora and Chad argue that their behaviors

make them an “odd duck.” In addition, although both ducks realize that they

feel concern about the other one, Chad reveals that he feels concerns for

Theodora being odd (even though Theodora asserts that Chad is the odd duck).

This section results in the reader wondering who was the “odd

duck” after all. Likewise, many

people with autism often see non-autistic individuals as the “odd ones,” since

all they have experienced is having autism, and are not always aware that

others consider them to be odd.

Seventh,

Theodora and Chad go their own separate ways periodically, with Theodora

realizing that she misses Chad. Likewise,

many people with autism often lose friendships because of behavior differences, and many people with and without autism who are

friends sometimes temporarily stop talking to one another due to those behavior

differences.

Finally,

Theodora realizes that she misses life being friends with Chad and decides to

reconcile with him. Chad accepts, they reconcile, and their friendship resumes.

Likewise, such reconciliations often

occur in friendships with and without autism.

The ending of the book—where Theodora and Chad reconcile and become friends—is not unrealistic, but sadly, does not always happen in real life. In many cases, after an argument like the argument in the book, a friendship between a person with and without autism sometimes ends. However, this is not inevitable, nor is it always the case. I admire the ending chosen for this book since this demonstrates, in the allegory presented, that these friendships are possible, and you can reconcile differences between people with and without autism in their friendships.

In addition, Odd Duck also is about a cross-gender friendship, a friendship between a male and a female duck. Likewise, cross gender friendships are quite common among people with autism, and many people with autism, because of social deficits and differing social expectations in our society, often find they have more cross gender friendships than same gender friendships.

Another unique parallel to autism that can be found in Odd Duck is the “gender gap” that is now widely discussed in the autism community pertaining to diagnoses of autism. In the story, Chad, the male duck, is identified and classified by Theodora and others as an “odd duck” due to his behaviors much faster than Theodora, the female duck, whose behaviors are also somewhat “odd” but not identified as immediately and identified by Theodora and others. In addition, Theodora’s odd behaviors are much more accepted and she does not endure the same social struggles that Chad does in fitting in.

Similar behavior patterns can be found in how males with autism are much more easily identified as having autism in comparison to females. This disparity was initially researched by Dr. Tony Atwood in 2006, and his findings suggest that there is a significant gap between the identification rate of males and females with autism. Females with autism are more likely to be misdiagnosed or undiagnosed with autism than males. Atwood’s research suggests that this may be, in part, due to cultural factors—it’s easier to identify behaviors of autism in males than in females.

Although Odd Duck has been marketed as a children’s book for ages 6 and up, the book has many features as a book for older children—it has chapters and is approximately 96 pages—longer than many other books for that age group. In addition, the book also describes many social issues and situations that are commonplace among individuals with autism. I personally was quite impressed to see how the authors accurately portrayed many of these situations in a way that is understandable to individuals of all ages. Issues portrayed in this book for children are issues I often teach and address in presentations for adults much older than the book’s intended audience.

I personally believe that this book is a good book for all ages. Despite being written for young children, this book’s message—the importance of accepting differences—can be understood and valued by people (and ducks) of all ages.

A related series of books including anthropomorphic animals that parallel social issues common among individuals with autism are the George and Martha book series. This series tells the story of two anthropomorphic hippos who are cross-gender best friends. Unlike the book Odd Duck, the George and Martha books are about an established friendship, but similar to Odd Duck, both George and Martha do engage in behaviors that can sometimes annoy one another. However, like in Odd Duck, the stories end happily—misunderstandings are resolved, and the friendship resumes.

Case Study #2: Gender Blender, by Blake Nelson (Delacorte

Press, 2006)

Blake Nelson’s Gender Blender is a book about gender differences in middle school. It uses a common fantasy plot device—the device used in the book Freaky Friday by Mary Rodgers and the series about Jake Sherman by Todd Strasser—the story of two characters who dislike one either having to endure their minds being switched into the other one’s body. In this story, a girl and a boy in middle school—Emma and Tom—who used to be friends but now are enemies, find that their minds have been switched into each other’s bodies due to a freak accident. Complicating matters is that this freak switch occurs while both Emma and Tom are partnered together to complete a school assignment about gender differences.

As the story begins, Emma and Tom do not get along, yet were friends in the past. We soon learn that Tom is primarily responsible for the conflict, and is extremely mean to Emma and her friends. We learn that this was not always the case. Emma and Tom used to get along, yet Tom has now changed. Emma is quite upset over this, and does not understand why Tom is acting this way towards her. She remembers the days when they enjoyed spending time with each other.

When an accident occurs in a baseball game between Tom, Emma, and her friends that results in him being mistaken as a pervert (which was indeed an honest mistake) Emma is unable to help her former friend. Later on, an accident on a trampoline between Emma and Tom results in their minds being switched into each other’s bodies. Later, the accident is discovered to be an awakening of a Native American curse, tied to one of Tom’s arrowheads.

Through the experience (and some embarrassing moments), Emma and Tom learn about the different expectations that society imposes on boys and girls, and the different issues that the other must go through. They also start to understand the pressures that caused them to stop being friends in the first place, which consisted, in part, of the disgust and disdain their same-gender friends had (but they did not entirely share) towards their respective opposite genders, and towards cross-gender friendship.

Interestingly, these pressures affect them differently. Tom appears to be more susceptible to them than Emma, since he is constantly putting Emma down and saying insulting things about girls, which is later suggested not to necessarily be a part of Tom’s nature, but because of the pressures that Tom’s male peers and others exerted on him. He appears to be more certain regarding those pressures, whereas Emma, on the other hand, is more confused. She hears the pressures that her female peers, especially the girl clique the Grrlzillas, exert on her, but does not take actions on them the way Tom does. She, rather, becomes quite unsure on how to respond to them.

Although Emma and Tom do end up switching back in the end, parts of the ending, however, are ambiguous—when Emma and Tom attempt to reconcile after their minds and bodies have been shifted back to normal, they still get into an argument that is not settled when the book ends.

What I like about this book is that it does not shy away from many of the personal, gender-specific issues of adolescence. Tom, in Emma’s body, initially enjoys being in a girl’s body (in part because he enjoys looking at it) but soon has to learn how to wear a bra and actually experiences Emma’s first period in her body as well. Meanwhile, Emma, in Tom’s body, has to cope with erections, and how to use the restroom as a boy.

These are the issues that every adolescent has to cope with as they enter puberty, yet our society often does not allow open discussions of these issues. I admire that this book discusses them freely. These issues are very uncomfortable for many people, and in many ways, not being allowed to talk about them just increases that discomfort for many people.

In addition, societal expectations are portrayed as well. Emma, as a girl, is expected to be obedient and values doing well in her classes, as well as working hard at piano, whereas Tom acts like the stereotypical lazy boy—he enjoys failing and isn’t even fully aware of what homework is, despite being in middle school. Tom is also expected to engage in dangerous activities with his male friends as well.

Although the book portrays many stereotypical tendencies of kids in middle school, and Emma and Tom both act in many stereotypical ways, the book does not endorse those expectations. Rather, the book shows the negative impacts that these stereotypes bring in the lives of kids, and how it can stifle the ability for people to get along. The book also shows how these stereotypes affect boys as well as girls, and suggests that many of the “bad, annoying” behaviors that boys exhibit are the product of this stereotyping, similar to how we associate many negative pressures exerted on girls from this stereotyping.

In demonstrating many stereotypical and conventional ways that middle school children relate to one another and are socialized, I got to learn about the vast differences in how children with autism are socialized versus children without autism. Many of the “conventional” experiences mentioned in this book are not often experienced by middle school-aged children with autism. I can speak of this thru personal experience. My social experiences in my elementary and middle school years were so different that I was not even aware of many of those differences until adulthood.

Many children with autism have social deficits and struggle with social skills and fitting in with other children. Whole curriculums have been made to attempt to correct these issues. However, what is not always acknowledged is that most children with autism, as a consequence of those social issues, are socialized differently. Most of them do not experience the same social “rites of passage” that most children to, or experience them at different stages in their lives. And these differences in socialization can further enhance an individual with autism’s social deficits.

One of the major social differences between many children with and without autism relates to cross-gender friendship. Although the conventional stereotypes are changing in today’s world, there is a strong tendency for children to view cross-gender friendship negatively. This stereotype is displayed prominently in the book. This book portrays most of the students viewing cross-gender friendship as an undesirable form of friendship. This mentality is often associated with many children, especially at this age, which has resulted in many professionals and teachers assuming that children will gravitate to their same gender for friendship, with the formation of stereotypical male “gangs” and female “cliques.”

In contrast, for many children with autism, it works the other way around. Many children with autism desire opposite-gender friendship, and/or, in today’s age of multiple gender awareness, friendship between people of multiple different genders. Many children with autism gravitate towards their opposite gender rather than the same gender. And interestingly, this social preference is often mutually acknowledged and accepted among non-autistic children—non-autistic girls tend to be more accepting of boys with autism, and non-autistic boys tend to be more accepting of girls with autism. In contrast, many of the “same-gender” cliques and gangs that form among non-autistic individuals often ostracize their same-gender counterparts with autism.

This was my experience growing up. I had mostly female friends, and although I had male friends as well, my best and closest friends were almost always female. I was shocked when I learned, in high school, just how undesirable so many of my peers viewed cross-gender friendship. To me, most of my friends were female, and still are to this day. Amazingly, the same girls who were my best friends judged my female peers with autism, and the same guys who judged me were the best friends of my female friends with autism. I always felt I related better to girls, and many of my female friends felt they related better to guys. Some of my female friends and I would speak freely about many personal subjects that are usually only spoken to among people of the same gender, and valued our ability to do so highly.

Unlike many non-autistic individuals, many individuals with autism value their cross-gender friendships highly. They often feel judged by their same-gender peers, especially in childhood and adolescence. They feel less judged and can be more of themselves with friendships of the opposite gender, and possibly friends of other genders as well.

A second difference that occurs between some people with autism and their non-autistic counterparts relates to conversation subjects and common interests. Children with autism tend to have different interests than non-autistic children. In this book, the boys and girls tend to talk about many interests common among their gender groups. Emma’s friends enjoy talking about boys, while Tom’s friends enjoy playing baseball and talking about sports. But children with autism are often interested in different subjects, and often struggle to understand why non-autistic children are interested in the things the way that they are. They often view the interests of non-autistic children as dull, boring, or illogical. Likewise, many non-autistic children feel the same way about things kids with autism like, which can cause many social conflicts.

Growing up, I often felt this way. I was non-athletic, and I also didn’t share the same “romantic interest” in girls the way my male peers did. As a result, I often struggled with relating to many of my male peers, who wanted to talk non-stop about how different girls looked, which downright bored and/or disgusted me.

In addition, although children with autism are often subject to the same gender expectations that all children are subject to, like Emma, those expectations often frustrate them. The expectations that Emma and Tom, and their peers, are subject to are very similar to the expectations that children with autism struggle with the most, and like Emma, they struggle with understanding them.

Likewise, the struggles that Emma and Tom experience in each other’s bodies, living as members of the opposite gender—as fanciful as they are—are actually similar to many of the experiences that people with autism have coping with the unique issues and expectations of the gender they were born with.

I personally enjoy this book since it discusses those two pertinent subjects mentioned above that are major parts of the lives of individuals with autism growing up: the subject of cross-gender friendship, which is a very common feature in the social lives of individuals with autism, and how boys and girls are given different social expectations when they are growing up. This book is a great book for anyone looking to further understand the differences gender brings in the overall experiences of middle school children, and at other stages of life as well.

A different, but related book that I also read that discussed similar parallels regarding gender differences and autism was Phyllis Reynolds Naylor’s Alice the Brave. This book, which is a part of the Alice series written by Naylor, also discusses gender differences and gender expectations. The story takes place over the summer, where Alice and her friends experience and endure these issues, and the social embarrassment that she experiences while her friends hang out at a friend’s backyard swimming pool.

Book Study #3:

6th

Grade Can Really Kill You by Barthe DeClements (Viking Penguin Inc., 1985)

For my final book study, I decided to focus on a book that I had enjoyed previously as a child, to compare how I viewed the book today versus how I viewed it in childhood.

Barthe DeClements’ 6th Grade Can Really Kill You is a book that I enjoyed immensely as a fifth grader. I enjoyed reading it since I felt like I could relate to Helen Nichols, the main character. In my opinion, many of her issues and experiences paralleled mine. For example, Helen often gets into trouble and struggles with her studies in school, traits I shared growing up with autism. And like Helen, who fails to get along with Mrs. Lobb but gets along better with Mr. Marshall throughout the story, I got along well with some teachers but not others.

The reasons for why I read the book now, as an adult, were quite different than when I read the book as a child. While researching at the CCB, I read it to compare how the experiences of a person with a different disability related to autism was portrayed in a children’s book, and how those experiences paralleled the experiences of a person with autism.

At the beginning of the story, Helen is starting the sixth grade, which, in the school district described in the book, is still considered part of elementary school. Junior high starts in the seventh grade. As her first day of school begins, we learn that some people have given Helen the nickname “Bad Helen” due to her behavior. We then see an example of such behavior—on that same day, after she learns she got Ms. Lobb as a teacher, she uses thread to put a trap in the classroom to trip her up in the classroom.

In another scene, Helen sneaks an alarm into the classroom and sounds it, which Mrs. Lobb mistakes as the fire alarm, and then subsequently has the students line up and the leave the room as if it was a fire drill. This prank demonstrates one subtle difference between Helen, who is learning disabled, and a person with autism who may be learning disabled—fire drills are very difficult for many people with autism to cope with due to auditory sensitivities. Although many children with other disabilities (and delinquent children) pull fire alarms and play pranks related to fire drills, a child with autism would be the last person to engage in such a prank.

Later in DeClements’ book, Helen is diagnosed with a learning disability, something I could relate to as well, since I have several learning disabilities due to my autism. This results in her being placed into a different classroom with a different teacher. This placement gradually results in an improvement in her behavior. Likewise, I went to an elementary school where there were vast differences regarding how specific teachers understood people with disabilities. I functioned much better in the fourth grade with an understanding teacher, in contrast with the second grade where I was miserable due to a teacher that did not understand my autism and I did not get along well with.

When I read this book as an adult, I also wanted to analyze and look at what I had “missed” while reading it as an “egocentric” child, many years later. I quickly concluded that I had missed a lot from the story.

Reading the book later in life, I still was able to understand how I related to Helen as a child. But there was a whole depth to the book that I understood now that I did not realize existed as a child. This book was not just about Helen, the “bad” child who misbehaved in class. It was also a book that taught awareness of something I was not aware of as a child, but am very aware of as an adult—the disparities that are common not just in diagnosing individuals with autism, but in how special education services are administered in our schools.

In a nutshell, many children with special needs have services, but not all of those children receive the services that they need. It is revealed midway throughout the book that one of the reasons why Helen has not gotten the services she has needed is because her parents have denied permission for her child to receive them, even when the school recommends that she receive them. This adds another dimension to the story that I missed as a child—the process that it takes, after Helen engages in multiple instances of behaviors, for her parents to allow and accept the reality that her child needs to access special education services at school. The book was not just about Helen, my adult brain realized—it was also about what sometimes is involved for parents to accept the reality of their child’s disability.

Another element of this book that I saw when reading it is an adult is the extent of how much the book describes the role a teacher can play in a student’s performance. In schools, there is a common tendency to blame the student for their own misbehavior. However, as educational theorist John Holt and others have discussed, sometimes, even when a student misbehaves, the problem lies not just in the student, but in the teacher as well. Sometimes the teacher can actually be at fault. And sometimes both the teacher and student are at fault together. Blame in a difficult situation may not always be one person versus the other.

In addition, with my professional background, I saw how Helen’s experiences in DeClements’ book parallel three common themes that occur with people with autism as they go through school:

First, different teachers, based on their understanding of autism and how well they work with the specific children with autism in their classes, impact a child with autism’s behavior and performance in a classroom differently, and that some children with autism can work well with some teachers but not others. Likewise, later in DeClements’ book, Helen’s performance and behaviors change significantly when she is transferred from Ms. Lobb’s classroom to Mr. Marshall’s classroom.

Second, how seemingly “problem” and “bad” behaviors from a child with autism can actually stem from years of people misunderstanding them and not attending to their needs, rather than intentional malice. The book initially introduces Helen as a bad child that has been given the nickname “Bad Helen,” yet later on, we learn that these behaviors are the product of years of being misunderstood and feeling disrespected by peers and teachers in school. Although the process is not immediate, the ending of the story—where Helen finally is able to change her behaviors after she has changed classrooms, demonstrates that even children who engage in bad behaviors, are able and willing to change their behaviors if they feel that others are treating them with the respect they desire and feel they deserve.

And third, that many academic struggles that children with autism face are not always the product of being dumb or lazy, and are in fact the product of learning deficits, indirect disabilities, and not being given the proper supports and services that are needed for those children to perform optimally in the classroom. Likewise, Helen does not become the best student in Mr. Marshall’s classroom, but she is more willing to learn in Mr. Marshall’s classroom because she feels more respected by Mr. Marshall, and because Mr. Marshall is more willing to understand her and help her. She initially considers Mr. Marshall’s classroom to be the “retard room” only to realize that the students there aren’t really retards—they just need extra help.

The book has a happy ending, however, which demonstrates the premise behind the story—kids like Helen are not inherently bad kids. After Helen is caught once again pulling a prank, Mr. Marshall’s willingness to help her rather than just blindly punishes her proves to be what Helen needs to take the first step to change her behavior for the better. When she realizes that Mr. Marshall truly cares about her, for the first time in many years, she shows restraint before pulling another prank—in this case, saving a firecracker for junior high. Whether or not she uses the firecracker in junior high is up for the reader to determine.

One other unique aspect about this book is that although Helen is diagnosed with a learning disability and not autism, the book was written in the 1980s—a time was autism was not as widely known than now. And Helen does show many autistic tendencies in the story—the most apparent being social deficits as she engages in many socially inappropriate behaviors during the story. And to this day, there are cases of individuals with autism who have been misdiagnosed as other disabilities, such as learning disabilities, before being diagnosed with autism.

In the end, regardless of Helen’s ultimate diagnosis, I enjoyed this book because of its timelessness—the issues that Helen faces, written in the 1980s, are still true today as they were back at the time this book was written, even though our schools are much more aware about individuals with disabilities. In addition, the message of the book apples not only to learning disabilities and autism, but to many other children as well—that children and adolescents need to feel respected by adults, and if we expect them to respect adults, we need to give respect as well. As the old saying goes: Give respect, get respect.

Unlike the other books that I read, this book was unique and therefore, I did not find a similar book in the collection related to the subject of this book.

Conclusion

The time I spent conducting my research at the Center for Children’s Books was an unforgettable experience. I read many amazing books inside the library’s collection, far more than the three books in this paper that I analyzed, but the three books I chose for the studies in this paper represented three main parallels to autism that I was looking for when browsing the collection.

Reading the children’s books at the CCB also helped me understand more about my unique childhood, and helped give me insights into the differences between my upbringing and the upbringing of other children growing up. I read about experiences in the lives of children that I myself never experienced, directly or indirectly, due to my autism. Common experiences among children, such as the “gender awkwardness” from Gender Blender, did not occur for me when I was growing up.

Finally, one thing in particular that impressed me when reading many books in the collection, especially books about middle and high school children, is the prevalence of many “taboo” subjects in such literature. In Gender Blender, for example, almost every issue from menstruation to uncontrollable erections was discussed.

In the end, many stories and scenarios in children’s literature parallel issues of autism. And this may suggest that many of those issues may not be specific to autism. They may, in fact, be issues that many children face, but are issues shown and expressed differently. Children with autism may also experience these issues with a different magnitude.

I would especially like to thank graduate assistant Alice Mitchell, who assisted me in recommending several books for my project and helped me throughout the project.